Philosophy, Duty, and Tragedy: The Trial of Socrates, the Conflict of Antigone and Ismene, and the Consequences of Moral Beliefs

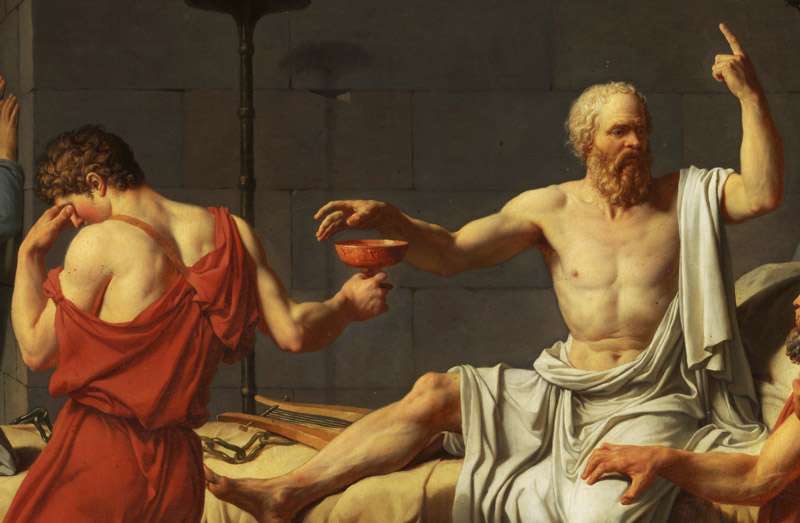

Socrates, a 70-year-old philosopher, was put on trial in 399 B.C. He was accused of numerous offenses of various kinds. At first, the judge had found Socrates culpable. However, because the law had not established a punishment for his offense, Socrates was forced to either recommend his own punishment or accept Meletos' suggestion of the death sentence. When it was time for Socrates to give his defense, he addressed each charge leveled against him one at a time in an effort to clear his name of wrongdoing. Socrates decided to refute the first charge that he had studied natural philosophy. Socrates was thus regarded as someone who aimed to replace mythical explanations of occurrences in the physical world with logical and scientific ones. On the other hand, a religious fundamentalist openly resisted this notion. One of these religious fanatics who favored the literal readings of Greek myths to the logical ones was Meletos, the prosecutor of Socrates. For instance, Socrates would describe a roll of thunder as a weather phenomenon, whereas Meletos would see it as an angry outpouring from the great deity Zeus. Socrates was accused of impiety toward the local deities as a result of these differing readings. Socrates "sought things under the earth and up in the heavens, and made the weaker argument stronger," according to Meletos.

Any attempt to use science to explain an event during this time was rejected because it was disrespectful to the gods and the Greek faith. Socrates was put on trial and accused of the offense of impiety. Impiety is the absence of respect for religious deities and other holy objects. Another important accusation was that Socrates was influencing the youth of Athens. Even though Socrates claimed to have a firm belief in the gods and even said, "The god has commanded me to examine men, in oracles and in dreams and in every which the divine will war ever declared," he was widely believed to be an atheist. (pg. 43). Socrates maintained his innocence and refuted each of these accusations. First, Socrates was judged guilty of impiety and given the death penalty. Socrates held fast to his conviction that he was not guilty of this accusation. He cited his belief in conducting divine deeds as justification for his assertion, saying, "And I think no greater good has ever befallen you in the state than my service to the god." (pg. 41). The false allegations in the charges of impiety are demonstrated by Socrates' reference to the gods and his conviction that he was doing virtuous deeds in their honor.

Socrates was falsely accused of being culpable, but he was still found guilty because he wouldn't defend himself and admit to his philosophical views. The impact of Meletus and his role in the investigation provided a second argument in favor of the claim that Socrates tainted the minds of young males. Meletus was viewed negatively by Socrates because of his ignorance, conceit, and immoral behavior. Similar to how Socrates felt Meletus' sophist relativism ruined any chance for real instruction. Even before the judges, Socrates asserts, "They know very well that Meletus is lying, even though he claims to be speaking the truth" (p. 43). Everyone seems to be against Socrates and his stance throughout this trial, but he stands by his opinions and never compromises on his convictions.

After analyzing the various crimes of Socrates It is evident that Antigone is guilty of corrupting the youth. Ismene is very different from Antigone because she is reluctant to defy her uncle's order. She does not acknowledge the gods in any way, shape, or form because she dreads the consequences of mortality. She makes mention of the "public good" and tells Antigone that rules are made for a purpose. Ismene seems to be making choices based on logic, whereas Antigone seems to be making decisions based on her feelings. Ismene does, however, promise to keep Antigone's strategy a secret after being persuaded by her sister. Antigone is enraged by this ostensibly faithful offer because she wants people to know the truth about her and her sister. Antigone believes her acts are entirely warranted. Ismene finds it incomprehensible why anyone would want to violate the law and publicly disclose this offense. But after the two meet, Ismene starts to think back on Antigone's arrogant actions when she realizes she might lose her sibling. As a result, Ismane requests to be charged with the offense of burying her sibling when she is brought before Creon, saying that she was aware of Antigone's scheme. She didn't want any part of this offense the day before, though. Ismene claims that she now knows what Antigone meant when she said she would honor her brother, a reality she initially seemed to grasp only at the thought of her sister's passing. Ismene displays compassion and devotion when she expresses how much she doesn't want to live without her sister, but the timing of her revelation raises questions about Ismene's moral character.

As the play's ending draws closer, Antigone and Ismene start to understand one another's opposing points of view. Antigone openly acknowledges her sister's perspective when she tells Ismene, "Your wisdom appealed to one world - mine, another" (88). She finally grasps the significance of life in Ismene's eyes. Ismene admits her wrongdoings to Antigone and tells Creon, "I share the guilt, the consequences too." (86). She finally realizes that perhaps her obligations to the living should not have taken precedence over those to her own sibling. Due to their divergent faith beliefs, Ismene and Antigone are both to blame for breaking their relationship. Although they reconcile, it's too late to save their marriage or even stop Antigone from dying. Because she thinks the deceased have more influence over her than the state's legislation, Antigone feels a greater obligation to fulfill her duties to them. Ismene holds the opposing viewpoint and respects the influences that life can have on her. Sadly, their divergent perspectives ultimately lead to the breakdown of their once-close relationship, which cannot be repaired.

Immediately after Creon has given Antigone her death sentence, Ismene informs us that Antigone is engaged to Haemon. Antigone's conviction would have little effect on her relationship with Haemon since her manipulation occurred in secrecy. Proving the innocence of Antigone would be beneficial for Haremon. Haemon gradually becomes more emotional before reacting angrily and telling his father, Creon, that if he goes through with her execution, he will also lose a son. Ismene informs us early on in the drama that Antigone and Haemon will wed. Despite this, Creon still wishes to exact revenge on his prospective daughter-in-law for killing her sibling and disobeying his commands. In the end, the romance between the two loves and Haemon's ensuing suicide would hasten Creon's realization of his own tragic faults.

Post a comment